During its “second wave” in the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan amassed wide support from residents of Caldwell and Hays counties. Ku Klux Klan #124 presided over Hays County, mingling with the people by hosting barbecues, holding parades, attending church, and donating money to law enforcement.

Mention of Ku Klux Klan #124 first appeared in 1922, in an article from the San Marcos Record from Feb. 22 of that year describing Sheriff George Allen receiving a payment of $100.00 from the KKK in order to purchase bloodhounds for police.

Spreading from San Marcos and toward San Antonio, the Klan initiated about 100 new members into #124 later that year. It quickly grew from there, with Klan #124 holding a large “open air initiation” with close to 1,000 Klansmen present. The San Marcos Record reported on June 16, 1922, that the ceremony took place in a large field two miles south of town – “under the glare of a 12-foot fiery cross” – with many people driving in from towns in the area to see it. The report notes that the road was “lined for a mile with waiting cars” where a robed figure at the gate let participants in.

On July 21, 1922, the San Marcos Record describes a crowd of 15,000 people gathering in San Marcos to watch 500 Klansmen march down Hopkins and onto San Antonio Street. The Klansmen rode down the streets on horses and in their white robes, carrying signs stating, “America Always” or “For Our Public Schools.” Alongside the riders, other Klansmen rode on a large float that carried an illuminated cross wrapped in electric lights. The parade commenced with the Klansmen giving a series of speeches which the crowd responded to with “tumultuous handclapping and cheering.”

On Aug. 18, 1922, the San Marcos Klan #124 announced another initiation ceremony for Aug. 28. It invited anyone who was interested to travel one mile out from San Marcos, and that the initiation would take place on Martindale Road.

On July 20, 1923, a letter was published in the San Marcos Record on behalf of Klan #124, which acknowledged their formation of an “investigating committee that sees to any wrongdoings.”

The letter states that “a secret force that no one will know who they are” will target “old negro lovers” and ends by affirming, “We believe in white supremacy, and we believe that white men should keep white men’s places.”

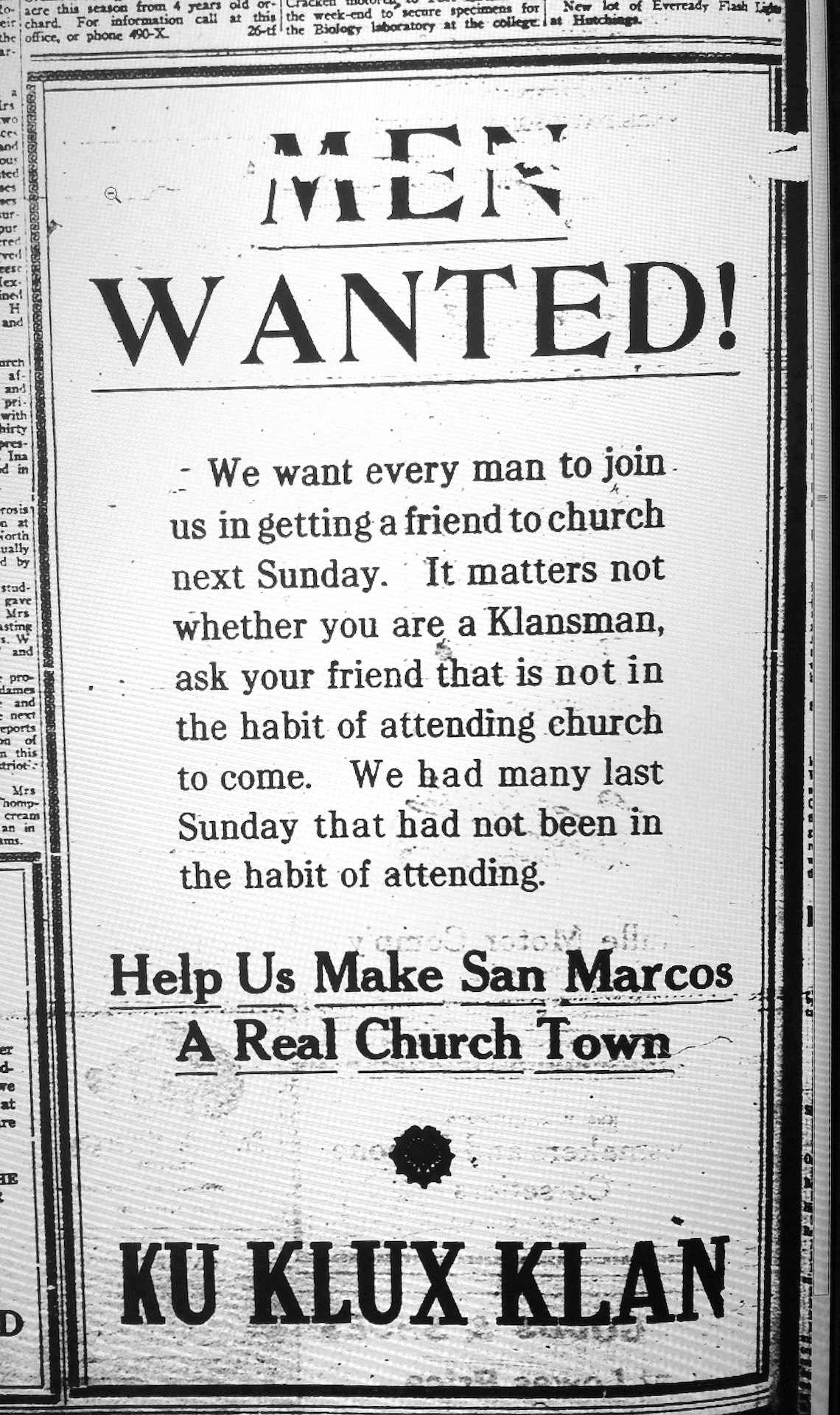

The local church was another place Klansmen found refuge in Hays County. On June 16, 1922, a bulletin for the Christian Church (located where today The Price Center operates) states that an unnamed minister will honor the Ku Klux Klan and invites those “who stand for true democracy and American principles” to attend the sermon. (This sermon occurred the same week as the open-air initiation with 1,000 Klansmen present.)

On June 23, 1922, according to the Record, Klan #124 attended Rev. D. A. Leak’s sermon at the Baptist Tabernacle and offered Leak a donation of $25, thanking him for “his kindly feeling for the Klan.” In response, Leak “heartily endorsed the Klan and its good work” – giving the floor to the visiting Klansmen, cloaked in white robes, to allow them to give “a short exposition of the principles as advocated and practiced by the organization.”

Perhaps the most shocking is the recent revelation that former San Marcos mayor Frank Zimmerman held strong ties to the Ku Klux Klan. Zimmerman moved to Hays County in 1922 and quickly established himself as a prominent figure in the community. He held a number of positions in the San Marcos Kiwanis Club, acted as a scoutmaster, and served on the city’s Chamber of Commerce board. He also joined the First Christian Church upon his arrival.

In 1949, Zimmerman was elected as San Marcos’s mayor; he is credited with bringing widespread improvements to the city’s infrastructure and buildings. A recent lawsuit over Zimmerman’s previous home opened the gateway to examining his past involvement with promoting the KKK through the Palace Theatre (now The Marc) and The Grand Opera House, both of which Zimmerman owned and operated.

“His appetite in the film industry was whetted even more after he saw Birth of a Nation,” the San Marcos Record wrote in a 1969 article on Zimmerman, chronicling how he first got interested in the motion-picture industry – a reference to the infamous film that portrays the Klan as heroic and contributed significantly to national growth of the white supremacist movement.

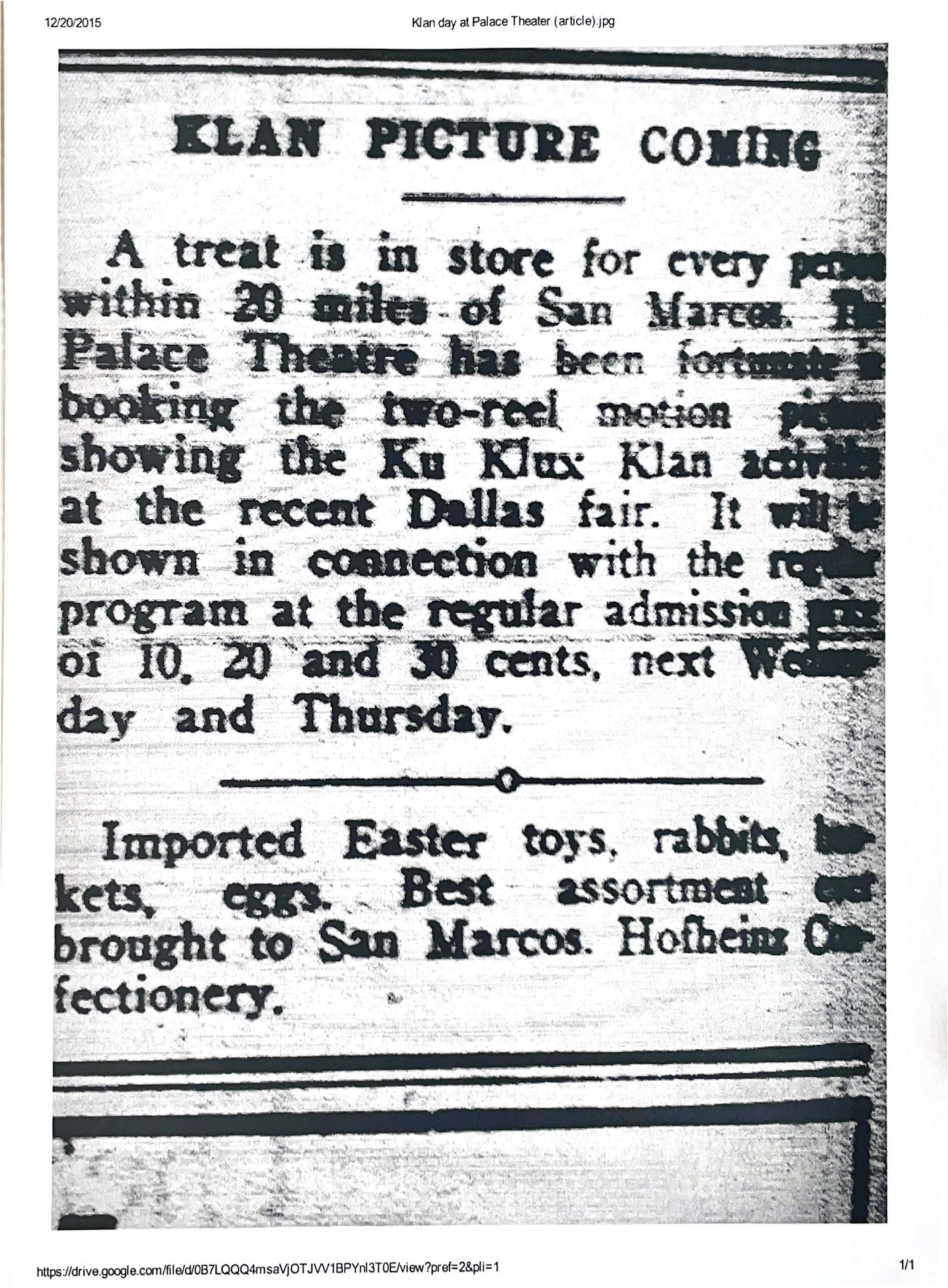

In a 1972 article, the newspaper praises Zimmerman as “instrumental in developing the movie theater business in San Marcos.” However, nothing indicates the racist past hidden within Zimmerman’s activities, such as when he hosted “Ku Klux Klan Day” at the Palace Theatre.

A Record article dated March 28, 1924, states, “A treat is in store for everyone within 20 miles of San Marcos. The Palace Theatre has been fortunate in booking the two-reel motion picture showcasing the Ku Klux Klan activities at the recent Dallas Fair.” A few months later, the Record reported that 20,000 San Marcans gathered that July 21 to watch the Klan march through the streets – believed to be the largest parade in city history, unmatched even by the annual, extremely popular, Mermaid Capital of Texas Downtown Promenade.

In 1972, Oct. 30 was declared “Frank Zimmerman Day.” Chamber of Commerce President Garland Warren stated on that day, “San Marcos will honor a man who has perhaps done more for this town than any man alive.”

Zimmerman’s promotion of the Klan may sting the most for those who grew up in San Marcos. He continues to have a positive reputation in the city; indeed, the only monument downtown honoring a municipal official is the tribute to Zimmerman in front of The Marc. Articles celebrating his contributions to San Marcos entirely omit his ties to the KKK.

The Ku Klux Klan continues to hold a sinister presence in Texas history. Hays County’s participation in that history has been shrouded by the passage of time and shame of those who participated in the Klan’s resurgence.

This is not a comprehensive list of the KKK’s activities in the San Marcos area. The San Marcos Record contains scores of articles discussing Klan meetups, calls for supplying barbecues celebrating the Klan, involvement with the church and law enforcement, and more. Regardless of the discomfort the facts may evoke, it’s undeniable that San Marcos played a large role in supporting the Ku Klux Klan’s growth and influence in Texas.

BY HAILEY M. STEWART

0 Comments