Elmo and Eli Zapata at the family’s body shop in Lockhart, photographed in May 2024 by Ursula Rogers

A little after 6 p.m. on May 30, 2022, several people were lounging by the pool at the Arba San Marcos apartment complex – among them, Hays County Sheriff’s Office Detective Jennifer “JB” Baker, who lived at the Arba at the time. One group of friends was listening to music and drinking beer – an ordinary way to spend a Memorial Day holiday at a place that bills itself as student housing – when the evening took a bizarre turn.

Baker, who was off-duty and had also been drinking, told them to turn their music down. When they wouldn’t, she told them the glass bottles they were drinking out of weren’t allowed by the pool. The group didn’t take a lecture from a random woman about the fine points of poolside decorum terribly seriously.

When Baker revealed that she was the complex’s so-called “courtesy officer,” her announcement failed to make the desired impression. She left the pool and returned in her HCSO uniform. This did not deescalate the situation. She continued arguing with one young man, Seth Riley, in particular, and tried to detain him. When he walked away from her, she pointed her Taser at him and told him to either get on the ground or she’d tase him.

At some point Baker called for backup to assist with the “disturbance.” The San Marcos Police Department officers who came to the scene wrote that when they arrived, Baker had Riley on the ground in handcuffs. Other residents and guests were yelling at the responding officers that Baker had been drinking. (Results of drug and alcohol testing taken later that evening would show that Baker was over double the legal limit for intoxication and also had amphetamines in her system.) Riley told officers that the experience of being threatened with a Taser was “terrifying,” and SMPD Officer Amber Wright observed that he had been “crying and shaking with fear,” and that he was “distraught and scared.”

One observer filmed the arrest and posted it to Facebook, where it went viral. Baker’s 15 minutes of local news fame came and went quickly that year, all of it focused on that single drunken incident by the pool.

However, a recently filed lawsuit accuses Baker of at least one other instance of “poor judgment” — one that caused lasting harm to a teenager and his family.

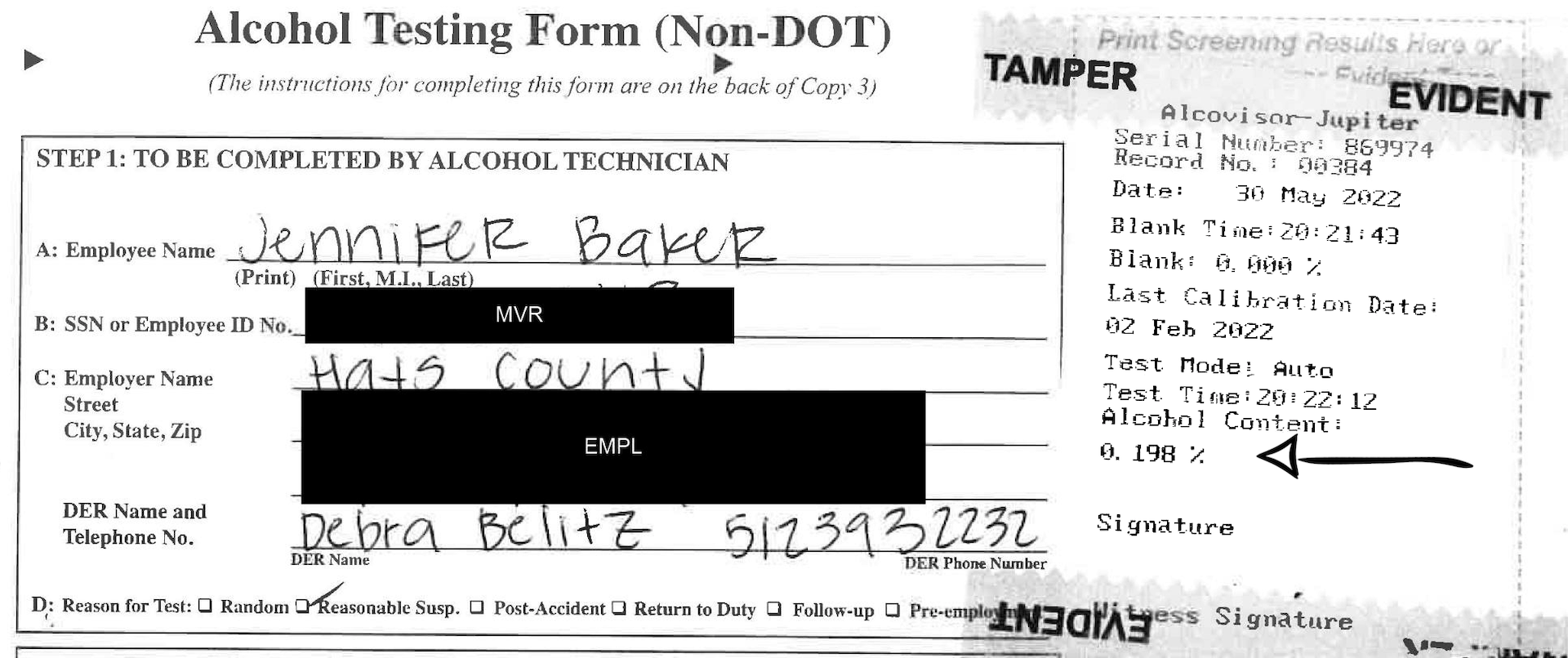

Det. Baker’s alcohol results, obtained by the Examiner via public information request.

Elmo’s Story

Emiliano “Elmo” Zapata is the younger of Elias “Eli” Zapata’s two sons and the only child Zapata and his ex-wife Janie Rebecca Loredo shared. Since his infancy, Elmo’s parents had realized he had certain developmental challenges, and he was later diagnosed as on the autism spectrum.

When Elmo was still in elementary school, Zapata and Loredo split up, and their divorce was finalized in 2014. Zapata remembered their relationship being characterized by volatile arguments made worse by Loredo’s alcoholism. But despite her faults, Loredo was devoted to Elmo and wanted what was best for him. She fought for Elmo to get the services he needed to succeed, even filing a lawsuit on his behalf while he was in middle school.

After her marriage to Zapata ended, Loredo began dating Philip Salyers, and she and Elmo moved into his house in Buda. Zapata said the environment at their home became increasingly strained over time. Zapata believes Loredo may have “been suffering from some type of mental breakdown,” and says that, by the end of the decade, Loredo “was getting arrested pretty frequently [for] domestic violence.” Hays County records show charges against Loredo for family violence spanning several years.

At one point in 2019, court records show, neighbors called CPS, and Zapata began the legal process to get legal custody of Elmo. (Both father and son say Elmo was never the target of Loredo’s violence, but that he frequently witnessed her fights with her husband and would even “call [Zapata] on the phone and ‘put the phone up’” so that his dad “could hear what was going on in the home.”) At the start of 2020, Elmo was spending much of his time with his dad and his paternal grandmother. However, he was still close to his mother and continued to go to her house to visit.

In April, Loredo let Zapata know that Elmo had gotten in some trouble for a Snapchat video that was circulating that involved Elmo and some of his cats. Loredo and Zapata went to municipal court with Elmo, who was ordered to pay a fine. The cats were returned to Loredo.

The situation at Loredo’s home continued to be increasingly fraught in Zapata’s estimation — he was on friendly terms with both her and Salyers — and he recalls telling Elmo in May of 2020, “there’s a lot going on over there, them fighting, and I really don’t want you going over there.” However, he respected the fact that his son wanted to spend time with his mother.

On May 15, 2020, Zapata recalls Elmo “started calling me around 6, 7 o’clock […] I didn’t answer because to me, I was like they’re fighting again, there was nothing new, I’ll go pick him up.” But “he kept just calling me and finally I was like you know what I better pick it up. So I called him back and […] he was frantic.”

A distraught Elmo told Zapata, “My mom is f***ing dead, Dad […] The f***ing house is burned down.”

Salyers later told investigators that Loredo had begun drinking at around 10p.m. and “continued drinking all night.” He says she kept waking him up as he tried to sleep. Elmo had avoided them by playing video games online with his friends in his room. At around 5:30 a.m., Salyers “couldn’t take the fighting anymore,” and decided to leave the house on foot — his car was in the shop. Elmo quickly followed him in his truck to pick him up and give him a ride to a gas station by the highway, where Salyers’s brother and father were going to come and get him.

When Elmo returned, the house was on fire. He tried to get inside to find his mom, but the flames were too strong for him. He began to scream for help, and neighbors called 911. When officers arrived on the scene, they put Elmo in the back of a patrol car, “for his safety.” He watched as firefighters pulled Loredo’s body from the conflagration.

Elmo, an excitable autistic teenager, was, as his father put it, “all over the place” after seeing his beloved mother’s lifeless body. As he waited in the patrol car, trying to reach his dad, Elmo was recorded calling various friends, and making statements that at times contradicted reality and revealed his limited understanding about what was happening.

“My house is gone, man. I ain’t got nothing left. My dad is going to jail for life, man, for the shit he’s done in the next few months […] My mom f***ing commit suicide or something. She went through with it.”

While Zapata had, in fact, been charged with a felony in Travis County in 2017, and pled guilty in 2019, he had been sentenced to probation, not prison. It’s unclear why Elmo thought his dad was going to prison, or if he was simply articulating a fear of his during a time of acute crisis, but Zapata believes that Elmo’s characterization of himself as someone who had “nothing left” made him a convenient suspect for the officers investigating Loredo’s death, one of whom was Baker.

After Zapata talked to Elmo, he immediately headed to Salyers’s home. The house was already destroyed when he arrived, but the fire continued to burn, despite the firefighters’ best efforts.

Zapata and Elmo spent hours at the scene, speaking to various investigators. Zapata recalls, “That’s when I met for the first time, Detective Baker […] And I kid you not, immediately when I saw her I thought to myself, ‘Man we’re gonna have trouble with this one, I already know.’ The way she presented herself, the way she walked, I just knew it.”

Preparing for the Worst

Zapata was wary of law enforcement. He told Elmo that weekend that the detectives investigating his mother’s death would want to talk to him. Elmo replied that he was eager to do so. He wanted to know what had happened to his mother. Zapata tried to explain to him, “You don’t understand how they’re gonna do, they’re not talking to you to try to help you.” He decided to illustrate his point by showing Elmo “Making a Murderer” and “When They See Us” on Netflix, both of which tell stories of teenagers falsely convicted of violent crimes.

Zapata says Baker called him that Tuesday, asking him to bring Elmo in to “ask him some questions.” He said that was no problem but that, “I’m gonna sit down with him because, one, he’s a minor and [two] he’s autistic.” Baker claimed it wasn’t “that type of interview,” but Zapata held firm. Finally, after going back and forth, he said, “I’ll have [my attorney] call you and I’ll have him set up a meeting with you.” His attorney told Zapata he’d work to set something up.

On May 20th, Zapata took Elmo to visit his grandparents. Afterward, “we got on the road and boom the vehicle came right in front of me, another one in the back and all the sudden they were from everywhere; they had us surrounded.” Elmo, a minor, was not under arrest for arson or the murder of his mother, but instead had been charged for the video he’d made in April.

“I kept yelling at him, ‘Do not talk to nobody!’” An officer told Zapata, “If you don’t want us to call your probation officer, you need to calm down.” To him this was more evidence that investigators saw Elmo as someone who wouldn’t have anyone to fight for him, but “from the jump, I said, ‘these people are not going to intimidate me.’”

The Juvenile ‘Justice’ System

While adult defendants receive bond hearings, things work differently for juvenile detention. As an article from the Texas District and County Attorneys Association explains, juveniles held in detention are given a hearing every 10 days to determine if further detention is warranted. While the court might impose specific conditions for release, it cannot set a bond for a juvenile.

Zapata hired criminal defense attorney Todd Dudley to represent Elmo. He recalls that at the first hearing, the prosecution claimed they needed to hold Elmo until he could be evaluated by a psychologist. Ten days later, the prosecution threw up another roadblock to Elmo’s release; they claimed a conversation he’d had with a friend the morning of his mother’s death was evidence of his intent to retaliate against one of the kids who’d seen the Snapchat video, and added another count to his charges. According to them, Elmo couldn’t be released because of this. As a consequence of his incarceration, Elmo was unable to attend his mother’s funeral.

At the time, the COVID pandemic was at its height. Law enforcement across the country was being urged to release prisoners, especially juveniles, who didn’t pose a danger to society in order to reduce the virus’s deadly spread within detention facilities. Yet Elmo continued to be held pretrial for an incident that had previously been resolved without any sentence of incarceration in municipal court and an accusation of retaliation based entirely on a conversation he’d had in the extremely panicked moments immediately after his mother’s death.

Various factors conspire to make juvenile detention centers particularly unfit for those with disabilities. As Zapata continued to fight for Elmo’s freedom, he also had to do his best to make sure the damage done to Elmo wasn’t compounded by a lack of access to services. Zapata worked with Elmo’s longtime educational advocate, Debra Liva, to sue the Hays County Juvenile Detention Center (HCJC), in order to force them to provide appropriate care for Elmo. The case was ultimately taken up by attorney Jordan McKnight.

That civil suit, which was first filed in June of 2020, is ongoing. During his time at the detention center, McKnight said, Elmo was repeatedly held in solitary confinement, allegedly for his “safety.” In July of that year, a portion of the suit was settled, and the center was ordered to provide appropriate educational services. Soon after, Elmo was finally released from custody.

But Zapata knew it wasn’t over.

The Arrest

As a condition of Elmo’s release, Zapata took him to the county courthouse every week to meet with a probation officer. When they walked in on Oct. 20, 2020, officers arrested Elmo for the murder of his mother.

According to Zapata, Dudley told him there was no point in arguing for Elmo’s release from custody for a murder charge until they were able to get discovery.

So each Saturday, Zapata would go to Dudley’s office to comb through the evidence with him. A timeline for Elmo’s trip with his stepfather to the gas station established that neither of them would have had time to set the fire before leaving. It’s possible Loredo, who had been drinking that night, had set the fire either accidentally or on purpose. The house wasn’t secured as a crime scene, however, and Zapata believes it would be hard for investigators to ever definitively point to the cause of the fire.

Instead, Elmo was charged with causing his mother’s death by hitting her with “a baseball bat or other unknown object.”

In her affidavit for a search warrant, Baker writes that an autopsy showed Loredo “had suffered multiple blunt force trauma injuries prior to the fire being started” that “were consistent with injuries that could be caused by being struck by a baseball bat.” But Baker also writes that “alarming photos’’ were taken from a search of Salyers’s phone, including one of him “wearing a green T-shirt with fresh blood splatter on the front of it.”

On March 12, 2021, Dudley questioned Baker over Zoom about what theories she may have had about Salyers’s involvement. According to a transcript, she replied, “One, that he was the assailant. One, that he left the residence and had no part of the assaultive incident as well as the fire. Another theory was that he’s the one that assaulted her with the bat potentially and then Mr. Zapata [Elmo] set the house on fire.”

Dudley asked, “Have you ruled out any of those theories?” Baker replied, “No, sir.” Yet Baker testified that although she’d shared these theories with the prosecutor’s office, she hadn’t written any of them down, preventing them from being turned over to the defense as potential exculpatory evidence.

Additionally, Baker admitted that in her directive to apprehend, she had said that Elmo had “returned to the scene of the fire as it was being extinguished,” but that, in fact, Elmo had returned before emergency services arrived. She told Dudley, “The time line’s off.”

Throughout her testimony, as Dudley questioned Baker about numerous inconsistencies in her various reports and affidavits, Baker repeatedly admitted she’d made some “pretty serious mistakes.” A custodial interview that she’d described conducting with Elmo at the scene in her directive to apprehend had not been documented in any previous reports, and she testified that her camera had not been on during it. She agreed with Dudley that “it’s unusual to conduct an interrogation of that sort with no video camera on.”

Dudley asked Baker, “There is no physical evidence whatsoever that Mr. Zapata committed this offense, is there?” Baker answered, “statements that he made.” Baker testified that Elmo had been unable to recall where he’d dropped his stepfather off and that “E.Z.’s story changed several times.”

Dudley asked, “And you’re basing your decision to arrest this young man and keep him incarcerated since October 15th based on his statements being different and mistakes?”

The Vindication

Why was Baker so determined to make Elmo out to be a murderer? Zapata thinks that she was trying to rebuild her career after a 2018 demotion. (Baker had been found to have “solicit[ed] a controlled substance from a subordinate,” and was demoted from sergeant to corporal.)

“She saw that the husband was white, well-to-do,” and “you have this troubled kid, troubled mother, it’s going to be easy.”

Zapata says “they were trying to paint him as a kid that had to get his way. He would throw a fit and rage if he didn’t get his way. Which, you know what? Maybe he would throw a fit but he never got his way.” Zapata explains, “He would calm down. I mean he’s autistic and there’s ways to talk to them.”

At the time of Elmo’s indictment, Wes Mau was the Hays County DA. As the Examiner reported in our cover story last month, and has been well-documented by other outlets, Mau’s office was often quick to indict. A March 2021 email to Dudley from Jennifer Howze, the lead prosecutor in the case, demonstrates the bias against Elmo wasn’t only Baker’s.

She writes that “the SRO [school resource officer] at Johnson High School” told her that a teacher who had been at Elmo’s school “heard that EZ was arrested and was not surprised, they knew something was wrong with him and that he would do something. He indicated that this teacher said that Rebecca would allow EZ to do whatever. [The SRO] also indicated that the mother sued the school and the district caved […] Just letting you know!”

The prosecution presented Elmo’s record from school as evidence of his propensity for violence. The criminal-ization of his behavior is not an outlier among students with disabilities. The U.S. Dept. of Education finds that students with disabilities are twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than those without, and they “represent a quarter of students arrested and referred to law enforcement, even though they are only 12% of the student population.”

Colleen Elbe of Disability Rights Texas says that they see clients as young as ten being charged with felonies for kicking or hitting teachers. “One of the problems is, if that’s on your record, you’ve kind of got that blemish and mark and you can be labeled a criminal for all the other intents and purposes in the community.”

Despite everything stacked against him, after seven months of incarceration, Elmo prevailed in his criminal case. The presiding judge refused to certify him as an adult after a lengthy certification hearing that Zapata described as basically a murder trial in the number of witnesses called and level of detail of evidence presented, and Elmo was allowed to go home. After years of persecution by Hays County, the murder charges against Elmo were finally dismissed with prejudice in 2023. Most of the people responsible had left Hays County at that point — neither Howze nor her co-chair Jeffrey Weatherford is a part of the current Hays County DA’s office.

As for Baker, her poolside actions on May 30, 2022, seem to have ended her career in law enforcement completely.

In the official investigation into the incident, several officers mention that Baker’s intoxication was obvious. HCSO Sergeant Kelly Woodward wrote, “I noticed that Corporal Baker was swaying slightly and her speech was slow and slurred.” HCSO Deputy Zachary Patton noted that Baker’s sunglasses “were messed up and not put on correct […] her pants were sagging and she did not have a belt on.”

Baker was taken for drug and alcohol testing that evening. Her BAC, recorded about two hours after the incident, was 0.198% (legal intoxication in Texas is 0.08 and above) and she also tested positive for amphetamines. Woodward wrote that as they were leaving, Baker “said something to the effect of, ‘how do you get fired on your day off, I can show ya.’”

On July 8, 2022, facing termination, Baker resigned from HCSO. On her paperwork, a handwritten note states, “not eligible for rehire.” A Recommendation for Discipline report lists three General Orders Baker was found to have violated and notes that a criminal investigation of official oppression was initiated but inactivated by the DA’s office.

However, Elmo and his loved ones’ fight for justice isn’t over. Elmo’s older brother Isaiah says that even though Elmo wasn’t named in news reports about the murder indictment saying that a minor had been charged for Loredo’s death, most people who knew him were able to figure it out. No press release was sent out by the DA’s office when the charges were dropped. This is the first time his story has been told to the media.

In addition to the ongoing case against the juvenile detention center, Dallas attorney Janelle Davis recently filed a lawsuit alleging malicious prosecution, intentional infliction of emotional distress and violations of due process against Baker, Howze, Weatherford and Mau, as well as HCJC and HCJC Administrator Brett Littlejohn.

“In a situation where there is ultimately a prosecution that happened and then it gets resolved in the defendant’s favor and they’re innocent of the crime then you potentially have grounds” for a malicious prosecution suit, Davis explained to the Examiner. “In this particular situation, what happened — particularly how long it dragged on and some of the judge’s comments in different hearings […] I felt like it was justified. […] The person left holding all this is Emiliano and he’s the one that deserves to be made whole as much as we can.”

The officials who wrote the 2022 report about Baker seem to view the incidents in 2018 and 2022 as anomalies in an otherwise admirable two decades of service. Lieutenant Clint Pulpan editorializes, “It’s sad to see her career tarnished by the two documented instances of poor judgment.”

Yet it’s hard not to conclude that Baker’s behavior throughout her investigation of Loredo’s death is a much starker example of that “poor judgment” than those other instances. It inevitably raises the question, is this simply a third anomalous case of “poor judgment” and “serious mistakes” in Baker’s two decades on the force, or are there others still that we just haven’t discovered?

After all, while almost no one had Elmo’s back, he had two tireless advocates in his dad and Liva. Without them, it’s easy to imagine Elmo being pressured to take a plea, locked away and forgotten.

“I told Baker, ‘you’re gonna remember me,’” Zapata recalls. “They tried to put me in jail for that, too.”

BY AMY KAMP

0 Comments