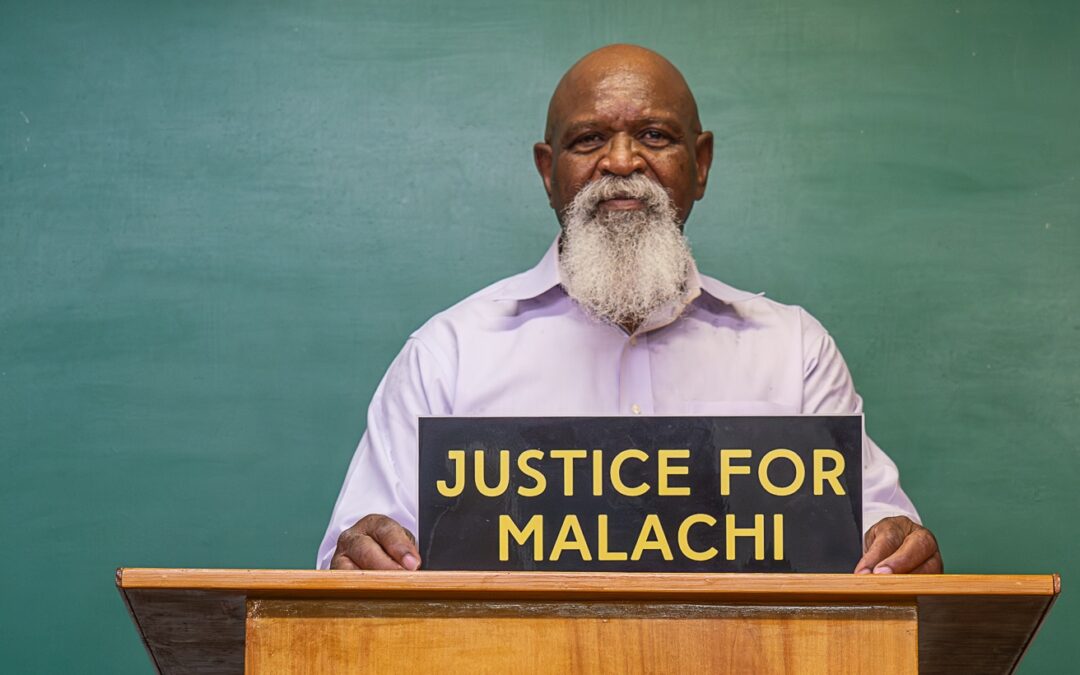

Pastor Wayne Miller, Malachi’s grandfather, stands in the sanctuary of his Lockhart church. Photo by Ursula Rogers.

For the past 6 months, I have had the honor of working closely with the family of Malachi Williams, a 22-year-old Black man fatally shot in the back by San Marcos Police officer Alcides Ventura in April outside the East Hopkins HEB.

You’ve probably heard his story by now. The day after it happened, it was all over local Facebook groups, then the media – first with the police narrative, then the voices of his family and advocates (as it usually goes). Since then, we have worked together to organize multiple press conferences and community events, spoken at city council meetings numerous times, and worked tirelessly to uplift the family’s calls for answers and justice for Malachi.

In October, on the 6-month mark of his killing, his family and I organized a press conference to release footage revealing that officers did not prioritize the rendering of medical aid (as required by department policy and claimed by Chief Stan Standridge) as Malachi laid on the ground, bleeding out. They even appeared to kick him.

Another video we released reveals what police’s account of events failed to mention: rather than “try to de-escalate” as Chief Standridge claimed during SMPD’s Aug. 16 press conference, Ventura unholstered his weapon outside of nearby Snax Max, prompting Malachi to run out of a rightful fear for his life.

I was asked to write this article to share what the new footage exposes, plus the difficulty the police department gave me when I requested the body cam footage, but I also want to reveal what working to support his family has looked like, because the tools to challenge those in power should not be consolidated in the minds and hands of a few activists who have the privilege of getting paid to do this work. We’ll never build a better world that way. Everyone should have access to these skills and this knowledge.

Apr. 11: An “Officer-involved Shooting”

On the night of Thursday, April 11, 2024, my boyfriend and I were driving home from the movie theater after watching the new Bob Marley biopic. The “Big HEB” looked like a crime scene: dozens of cop cars, flashing lights, yellow tape, roads closed. I rubbernecked from the passenger seat, thinking, “There’s definitely a death involved.”

The next morning, it was all over Facebook. “Man running with machete.” “Tyga concert.” “Someone stole UPD’s horse.” The rumors spread like wildfire. Only a handful made mention that a man had been killed by an officer. As the longtime communications director of a nonprofit, Mano Amiga – that has worked to hold local law enforcement accountable for wrongdoings since before 2020 – I pulled together each comment that sounded like a direct witness and texted them to every journalist I knew.

For years, I have seen firsthand how much turnover there is in regional media. Reporters do the work of five people – researcher, cameraman, interviewer, editor, etc. – for astonishingly low pay. So I try to be helpful; I sent them these links so they could speak with and publish the words of direct observers on top of whatever the police would later release. Shannon West of San Marcos Daily Record, one of my favorite journalists, did an awesome job of connecting with and interviewing witnesses.

As expected, many news articles the next day referred to Malachi’s killing as an “officer-involved shooting,” and simply regurgitated the narrative police and the Combined Law Enforcement Association of Texas (CLEAT) – which was immediately called to the scene to do damage control – put out. (CLEAT also handled rapid-response communications when a Hays County Jail guard likewise fatally shot someone in the back: Joshua Wright in December 2022. Its leader falsely tweeted Joshua had “grabbed a sharp medical object.” After the Examiner called them out, CLEAT leadership deleted it and changed it to “moved toward” a sharp medical object.” Similarly, after SMPD killed Rescue Eram, the department stated he ran toward officers with a “knife or similar object,” which the Examiner discovered, via open records, was a screwdriver.

Bottom line is local law enforcement have a lengthy track record of covering up their wrongdoings, either by flat out lying or leaving out critical details. There is always more to the story.

At this point, I had heard from different sources that Malachi was unhoused and struggled with mental health issues – which the police failed to include in their initial press releases. After I posted on behalf of Mano Amiga about the tragedy and challenging the police’s narrative, someone named Joseph commented saying he knew Malachi and asked us to reach out. We had lunch the next day. Joseph worked at the AT&T store around the corner from the Thai place where we met. He told me Malachi slept very near to the restaurant, and he would often buy him food and cigarettes. They’d watch One Piece, Malachi’s favorite anime, together. I learned a lot about Malachi’s character during our conversation, and a worker at the restaurant told us police had made Malachi move away from the building about a week prior.

I told Joseph I wanted to contact the family to see how our organization could support them and see whether they’d be interested in holding a vigil to honor Malachi and humanize him, which the police’s telling of events most assuredly never does. Together we were able to find a Facebook account for Malachi’s sister, Kay, and I reached out, introduced myself. I could tell she was skeptical at first, which is completely valid. But she agreed to meet with me and a colleague, and she brought her mom, grandpa, and three sisters. We would have to work to earn their trust.

Malachi’s mom, Ms. Shanta, opened the space by telling us how special Malachi was:

“My son was intelligent and a free spirit. He loved animals, loved to game, skateboard, read … he was a philosopher, really. He’d been reading since he was 2 years old, and he graduated high school at 14. He was funny, and he stood up for people’s rights. He was an awesome kid.”

Tears streamed down our cheeks as I awkwardly typed, wanting to capture each of her beautiful words so that other media could publish them exactly, too. She continued: “He participated in helping the unhoused before he chose to live outside himself – he just loved to be outside – and he stood up against police brutality in 2020 – the very thing that killed him. I was getting ready to take him to a psychiatrist and a beautiful new home in a new town in May. He was about to start a new life and finally get a chance to pursue his musical talent. Now he’s gone.”

We continued to meet. They showed me the new home into which Malachi was set to move. Watching home videos and hearing the family’s stories, I almost feel like I got to know Malachi personally. And, together with his family, we planned the vigil.

Blue and yellow everywhere, ice cream sandwiches, One Piece and other manga gear, a slideshow with pictures and videos of Malachi – we discussed all the different ways we could make this vigil a celebration of his life and all the things he loved.

It was a great success; more than 100 people attended and more than a dozen media outlets covered the event. Everyone in our community got to see for themselves how wonderful, bright, and soft of a person Malachi was. He was deeply loved.

In the months afterward, we spoke at several city council meetings to reiterate the family’s three main demands, including release of the body cam footage with all siblings and an attorney present. Public release of the footage was unfortunately out of the question – at first due to lack of political will, and later due to the department’s new Crisis Communication Policy, which solidified that, stupidly, criminal proceedings for the officer who killed Malachi must conclude first.

Family and friends of Malachi Williams stand before a Black Lives Matter mural after handing out hundreds of flyers in San Marcos to invite the community to an August vigil. Photo by Sam Benavides.

The Fight for Body Cam Footage

On Aug. 14, the Hays County District Attorney’s office announced that a grand jury had returned a “No Bill” for Ventura’s killing of Malachi, meaning he was cleared of all criminal charges – and the footage would now be subject to public release.

Immediately, I submitted an open records request for the body cam and convenience store footage. This wasn’t my first time submitting a request for body cam. I was familiar with the state statute, which requires that the request include the date, time, approximate location and a subject of the footage. I provided all these details, asking for footage from the four officers on scene.

Ventura was the only officer publicly named, but Chief Standridge mentioned three additional officers had been on scene when shots were fired. I also knew someone sent the Examiner witness footage, documenting how police mistreated Malachi after he was shot. In that video, Ventura walks away from Malachi shortly after firing, so I knew his body cam wouldn’t show the abuse Malachi endured following the shots. It was absolutely critical we got footage from all four officers.

Imagine my frustration – having helped multiple individuals obtain body cam in the past – when SMPD wrote back asking me to name the four officers. As aforementioned, state statute only requires that I name a subject of the film, and at that point, only one officer – Ventura – had been publicly named.

Perplexed, I asked Karen Muñoz, local civil rights attorney and organizer, to represent me, emailing the city with these points on my behalf. We’d also planned to join Malachi’s grandpa, Pastor Wayne Miller, in speaking at the City Council meeting that evening, so I knew exactly what I’d be speaking about.

Now imagine my confusion when, immediately following my public comment, Chief Standridge text messaged me a screenshot of my correspondence with SMPD, which I had just finished speaking about.

He wrote, “This is actually what you were told, and I will now share the law. It is forthcoming,” and followed up with the state statute outlining the requirements, which, again, I already knew. “The law. You have to name one of them, and you absolutely do know the name of one of them. I will inform Council tonight of what actually occurred.”

Puzzled, I replied “I’m sorry, I’m not seeing where it says I need to say the officers name? They’re asking me to list which officers I want footage from. I only know the name of one of them.”

He responded, “It only requires one of the names of the involved subjects, which in this case are the officers. You have that one name.”

I said, “Does subject not mean the individual who is seen in the recording? And what I’m requesting is footage from all four officers.”

I think he realized his understanding of “subject” was incorrect because he didn’t answer that question; he pivoted to instead explain that the cost will be “very high” (again, as if I’ve never requested body cam footage before) and said, “I’ve directed staff to fulfill your request after providing you notice of costs associated with redacting the videos pursuant to law.”

Never in my past experiences of requesting body cam footage has someone from the department reached out via text to explain that it’s going to be expensive. They just send me the invoice. In this case, the “very high” cost only came out to about $140.

After obtaining legal representation in this request, snitching to the police department’s bosses via public comment, and this bizarre chain of texts with the police chief where I proved his understanding of the law incorrect, SMPD sent me the body cam and convenience store footage on Sept. 6.

The footage was beyond difficult to watch, and I took in most of it through my peripheral vision. We already knew, through the Examiner’s witness footage, that rather than prioritizing the rendering of medical aid, for three full minutes officers instead turned Malachi onto his stomach, handcuffed him, turned him back over, and searched his pockets.

What I wasn’t prepared for was the way that officers continued to berate Malachi after shooting him. At first they all just stood there, pointing their guns at him, as he laid on his back with his hands raised. Ventura then approached, shouting, “Don’t make any sudden movements!” as Malachi just laid there. Squirming. Choking on his blood. Right before he’s directed to walk away, Ventura yells, “I told you to put your hands behind your back!”

Malachi was dying, and rather than showing empathy and compassion, or honoring the “sanctity of life,” as the department’s Use of Force policy proclaims they do, it was as if Ventura was telling him he deserved to be shot because he didn’t put his hands behind his back as told. In the footage, I also noticed that an EMT asked an officer to undo the handcuffs because they were getting in the way of life-saving measures. He looked so uncomfortable laying on his back with his hands tied. It breaks my heart that some of Malachi’s final moments were spent with people who treated him with such callousness. He hadn’t hurt anyone. He didn’t deserve that cruel treatment after being shot.

Unholstering ≠ “De-escalation”

Perhaps the most shocking moment of all the footage was outside the convenience store, because it revealed a vital detail the police had failed to mention in every wave of media coverage since April. While Chief Standridge had praised Ventura for attempting to “de-escalate” the situation, the SnaxMax footage shows Ventura unholstering his gun, which we believe prompted Malachi to run out of fear for his life.

Today, despite learning of Malachi’s kind, timid character – and how he was a full person with a full life and a deeply loving family who is still grieving – people continue to say things along the lines of, “Well he shouldn’t have ran.” I understand if the people typing these soulless comments feel that they personally wouldn’t have run. That’s great for them. But imagine an officer approaches you, begins giving you orders, telling you to put your hands behind your back, and won’t tell you why despite your multiple questions. You step outside and there are multiple cop cars waiting for you. Then this officer proceeds to pull his gun out from his holster. How threatened would you feel?

Now weigh in the factors that you are a young Black man, you are unhoused, and you struggle with mental health. It’s difficult to conceive of a scenario where someone in that exact position (no matter how much SMPD downplays his mental health challenges) would react in a calm, compliant manner, especially having just been displaced by cops from where he had been staying for months. How is unholstering your gun “de-escalation”?

It also continues to unsettle me that we know Malachi had several previous interactions with SMPD. Why, despite controlling the mental-health conversations, did they not get him the help he needed? I’ve attempted to seek more information, but the city refuses to turn over documentation from Malachi’s interactions with SMPD, citing state statute that exempts them from releasing information that is “highly intimate or embarrassing” or that is “not of legitimate concern to the public.” Because, as we’ve seen over the past six months, SMPD cares so deeply for Malachi’s dignity that they are willing to villainize him in order to solicit “great job smpd!” comments on Facebook. I believe it is of legitimate concern to the public to know what those previous interactions looked like and why those who are sworn to protect and serve let Malachi’s situation get to this point.

On Oct. 12, Malachi’s family held a press conference to release this footage to the community. Before it began, they distributed dozens of meals to our unhoused neighbors – a cause for which Malachi cared deeply. They told me they plan to continue feeding our community regularly, and they show no signs of slowing down in their journey to fight for justice for Malachi. Although I am no longer with Mano Amiga, now working full-time with the Examiner as Managing Editor, I am committed to continuing to support and uplift their efforts, and encourage you to follow them @family4justice on Instagram for more information on their upcoming calls to action.

To quote his favorite manga: “When does a man die? Is it when he is shot in the heart with a pistol? Is it when he’s stricken with a deadly disease. No. It’s when he is forgotten. I may disappear, but my dream will live on.”

Malachi, you will never die.

BY SAM BENAVIDES

0 Comments